Jargon Busting - JPG vs RAW

Mar 03, 2023

Welcome to the second entry in our new series of jargon-busting posts, aimed at those of you just starting out in your photography journeys. In this series, we’ll be attempting to demystify some terms that you’ll hear being bandied about in photography circles that might leave you scratching your head.

These are concepts it will help you to be familiar with and which we’ll be explaining in broad terms in order to develop a general understanding, without getting bogged down in the technicalities.

This time, we’re looking at the differences between shooting in JPG and RAW formats, and what this means to our pet photography.

The general gist:

- RAW files contain far more data than JPGs

- Capturing RAW files leaves the artistic choices to the artist

- RAW files are generally far larger than JPGs

- RAW files are usually not shared with clients outside of some commercial agreements

- Opening, editing and saving JPGs degrades their quality

Let’s take a moment before diving deeper and repeat one of the things that we mentioned in the previous Jargon Busters post.

There will be people who try to tell you that “professional photographers” always shoot RAW. That if you shoot JPG, you are not a professional. As we said in our earlier post on full frame vs crop sensor cameras (link), this is simply not true. We believe that shooting RAW is the best choice for pet photography in natural light, and won’t try to hide that fact - in fact, we’ll be giving you all the reasons why we believe this to be the case as this post progresses. However, there are reasons in other genres (outside the scope of this blog) that mean that shooting in JPG may not be the horror that some people believe it to be.

We encourage you, always, to keep an open mind, and when you hear a polarising statement, look beyond that and realise that everyone has their own application, so their own needs. That said, let’s get this show on the road!

To understand the difference between capturing your images in RAW or JPG, let’s go right back to the very start and investigate what happens inside your camera when you hit the shutter.

During that split second when the shutter is open, an image of the scene is funneled through your lens onto the camera’s sensor, as pure data. Regardless of whether you are shooting in RAW or shooting in JPG, the image starts off life as a set of ones and zeroes. Nothing like an actual photograph!

Those ones and zeros contain all kinds of information about the image and determine the exposure, white balance, contrast, sharpness, noise and anything else you can think of.

Think of it as your camera heading to the grocery store and grabbing everything it could possibly need to bake a cupcake. All the ingredients are stored right there in that temporary file that it creates when you hit the shutter.

Depending on what you choose to “shoot in” (RAW, JPG or even both) will determine how that raw data is collated and what type of file is actually saved onto your memory card immediately after the image data is captured.

Most modern DSLR or mirrorless cameras will allow you to select which format (or formats) to shoot in, with a range of sizes and qualities available for capturing a JPG image.

So what happens when you shoot in JPG?

Your camera (with a little input from the settings you choose - more about those later) instantly decides on a recipe to use, goes ahead and converts all that data into an image file called a JPG, and saves it on your memory card - ta da! Done!

So all those raw ingredients? It’s selected the ones that it wants to use, and baked those ingredients into the finished cupcake. It’s a pretty basic cupcake and there’s no icing. And how wasteful - all the unused ingredients are simply thrown away!

The problem is, if your camera forgets to add the sugar, or if the cupcakes were left in the oven for a bit too long and are burnt on the bottom, you’re pretty much stuck with the result. You can’t add sugar into a baked cupcake, and all you can really do is cut off the burned bit on the bottom, which isn’t great for presentation! And you can probably add some icing later, but the cupcake itself still tastes pretty plain.

So what’s good about a JPG?

Just like cupcakes, JPG files are easy to package up and share with people. Some cameras can even share the images wirelessly straight to your phone. They are generally small files that don’t take up much space on your memory card or hard drive. They can be instantly uploaded to social media, displayed on a website, and viewed on any device, without you needing to convert to a different format.

The most important factor is that they will look the same on every piece of software and device they’re opened on (without falling down the rabbit-hole of screen calibration for now).

JPG’s are great for all those reasons, but they have to be properly baked to result in a nice end result.

Now let’s look at what happens when you shoot in RAW.

We’ve already learned that when the image is captured by the camera, it’s actually just collected a stack of raw information from your camera’s sensor. When it creates the RAW file, it loads all those ingredients into shopping bags full of everything you could possibly need to bake a cake - or any other type of delicious baked goods you can think of - and hands them over!

So a RAW file isn’t actually an image file at all. Rather, it’s a data file! The image you view both on the back of your camera, and on the computer, is just a very simple visual interpretation of the data so you can see what you’ve captured. It’s not a finished image (or a nicely baked cake) at all.

So what do we do with all these raw ingredients?

Loading that RAW file into an app or computer program that understands all that raw data (like Lightroom or Adobe Camera Raw) is just like entering the kitchen, arms laden with bags full of ingredients.

Straight from the camera, we have all the ingredients in the RAW file to make a wide variety of choices on how to present the final image.

Join us in the Unleashed kitchen! We’re donning our aprons and are about to start baking. In front of us on the counter we have everything we might need to create any sort of baked deliciousness. There’s three types of flour, baking powder, sugar, salt, a box of eggs and a packet of butter. There’s jam, buttercream, icing, chocolate chips and sprinkles.

Now for the fun part - it’s up to us to choose which elements we want to include, how to put them together, and how much of each ingredient we want to use. Are we making cookies, muffins, or a Victoria sponge cake? What decorations are we going to add? All the time these ingredients stay on the counter, they have the possibility to be turned into so many different things. Likewise, our RAW file is full of potential, with so many possible ways we can process it.

Of course, in a real life kitchen, as soon as we start to play with our ingredients, they’re forever bound together. With RAW files, this isn’t the case. Our RAW editors are really smart - what they do is allow us to test things out without actually changing the underlying RAW file. When we add a bit of this (warmth, say), and mix in a splash of that (extra contrast, perhaps), we see on screen a preview of what our final baked good will look like, but all they’re doing is writing the recipe. They’re not actually mixing anything while we play, and the editor isn’t actually changing the original RAW file at all. If we decide after adding a whole host of ingredients that, in fact, we would rather have less warmth, we can take it out again without any penalty.

We can move those ingredient sliders as much as we want, previewing what the end result will be on the screen, but if we accidentally add a little too much of something, no bother, because we’re only writing the recipe. No eggs are being broken.

Once we have tweaked our recipe enough to have the perfect end result, we can tell Lightroom to bake that baby up into our JPG, and export it for sharing.

In this JPG export of my edit, I chose the elements of the RAW data to give this beautifully soft, warm image. Raising the shadows on the dog, adjusting the white balance to bring out the golden tones in the photo, the result feels calm and peaceful.

The RAW file, though? That’s still the same as it was when it came out of our camera. And our recipe is still there in Lightroom, ready to bake as many more duplicate JPGs as we want. Or, if we decide the next day that, actually, the final image could do with a little more or less of something, or we want to go in a complete different direction, we just go into Lightroom, tweak the recipe and bake another JPG.

Applying a different “recipe” to the same RAW ingredients completely changes the feel of the image. Which version is “real”? They both are! The camera captured all the data shown in both of these versions, and I can choose which ingredients to mix into the final version: cookies or cake?!

Even smarter than that is, for one RAW file, you can choose to have multiple recipes! You’re not restricted to one recipe per RAW file. There’s a feature in Lightroom called Virtual Copies which allows you to make as many different recipe cards for any RAW file you want. But that’s a topic for another day…

Since they include allll the ingredients you might possibly need for your recipes, RAW files are far bigger in file size. This makes them more cumbersome to share and most non-photographers won’t have the software on their computer or phone to even view a RAW file, much less edit it. And, even those that do, every piece of software that renders it can make it look different, because that rendering software is choosing the recipe!

And even if we were to share the RAW, tell the other party to use the same RAW editor as we do and provide the recipe for them (which would only allow that single person to see it as we do, and is still not shareable) - is this something we really want to do? Does Mars give consumers their recipes and allow them to produce their own, slightly tweaked, Mars Bars? Or do they believe that the way they have created their product is true to their vision and is the way it should be enjoyed? As photographers, we get to choose exactly how our images should look, and sharing in a “baked” format such as JPG lets us do that.

We know you must have some questions by now, so let’s dive into those.

How is it that we see an image on the back of our camera, when we shoot in RAW, if RAW files aren’t actually images?

This is a great question and you may already have guessed at least part of the answer. The answer is that, in order to display the photo on your screen, your camera renders the RAW file to a JPG. In fact, this preview JPG is stored inside the RAW file, alongside all the rest of the data!

That rendered JPG is displayed on your camera’s screen and used for the super-fast rendering of previews in software like Photo Mechanic. Different manufacturers store this JPG in different ways, and it may not always be a full-size image (Sony, we’re looking at you), but it allows a preview of what you might be able to extract from your RAW file.

Is the preview on the back of the camera an exact representation of what’s in the RAW file then?

Well actually, no!

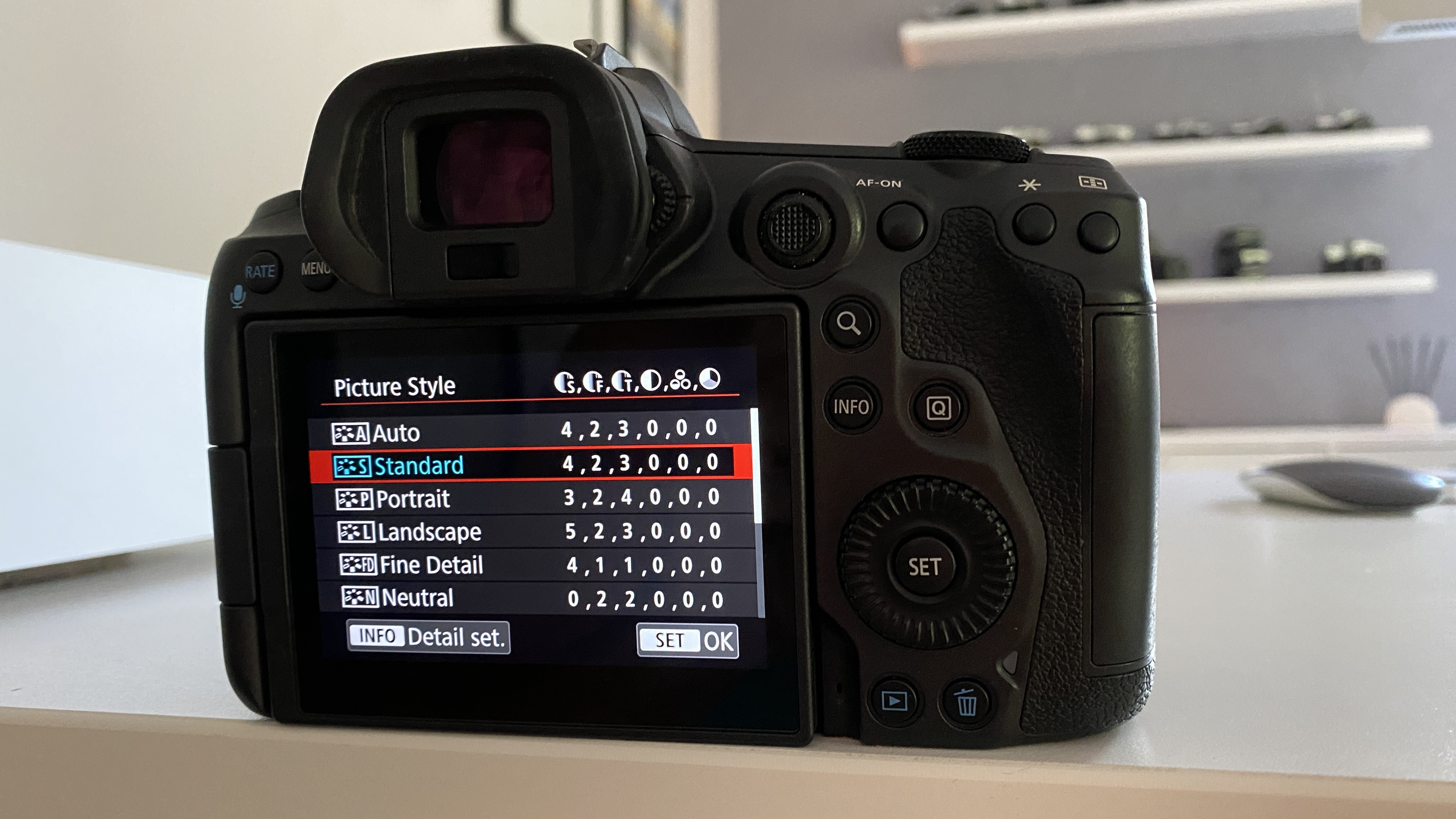

In your camera’s settings, you’ll have noticed that you can choose various “looks”. For Nikon, this is called Picture Control, Canon calls it Picture Style, and Sony calls it Picture Profile. The list varies between manufacturers, but includes options like neutral (very flat-looking image), portrait (designed to improve skin tones), and landscape (adds vibrant colours to landscape images).

On this Canon R5 camera, the option is called Picture Style. It shows you what adjustments each option makes to the RAW data to create the JPG preview, or “bake” into the JPG file if you choose not to shoot in RAW.

You can also choose additional settings like lens corrections, noise reduction and sharpness enhancement. Then, there’s white balance! Whatever the white balance is set to when the image is captured, will be what you see applied to the preview image on the back of the camera.

When shooting in RAW, these settings are not actually applied to the RAW file, because that would involve some baking, and we know by now that RAW files are simply a collection of raw ingredients. When we choose these settings, we’re simply choosing how the images will look on the camera’s screen, and what gets baked into that preview JPG mentioned above. All the raw ingredients are retained so we can bake them up however we like later.

But if we’re shooting in JPG only, that one colour profile has to be right for every photo we use it for, because that’s where we choose if we’re going to be creating cakes, cookies, pancakes, or some random British dessert that has to be drowned in custard before it’s vaguely palatable. This recipe is being applied and baked in-camera, and once it comes out of the oven, there’s no going back. You get what you get, whether you like it or not.

Neutral is a very flat image with little tonal contrast. Standard has just a touch more saturation and “punch”. Look at the legs of the dog and you’ll see how the Portrait profile has added in more red for skin tones, and the Landscape profile has boosted the oranges - a lot!

Again, the Neutral profile gives us a very muted, flat image. Standard is a lot warmer and with more contrast. Check out the tongue in the Portrait version to see how this really puts a lot of extra emphasis on skin tones, and the dog overall looks a little pink. Finally, the Landscape profile has boosted the warmth in the background, but has also over-saturated the dog, making her look way more pink/orange than she actually is. If you shoot in JPG, one of these will be your final version. But with RAW, we can choose any of them, and switch between them in Lightroom to choose the best one on a per-image basis!

So which colour profile should I choose?

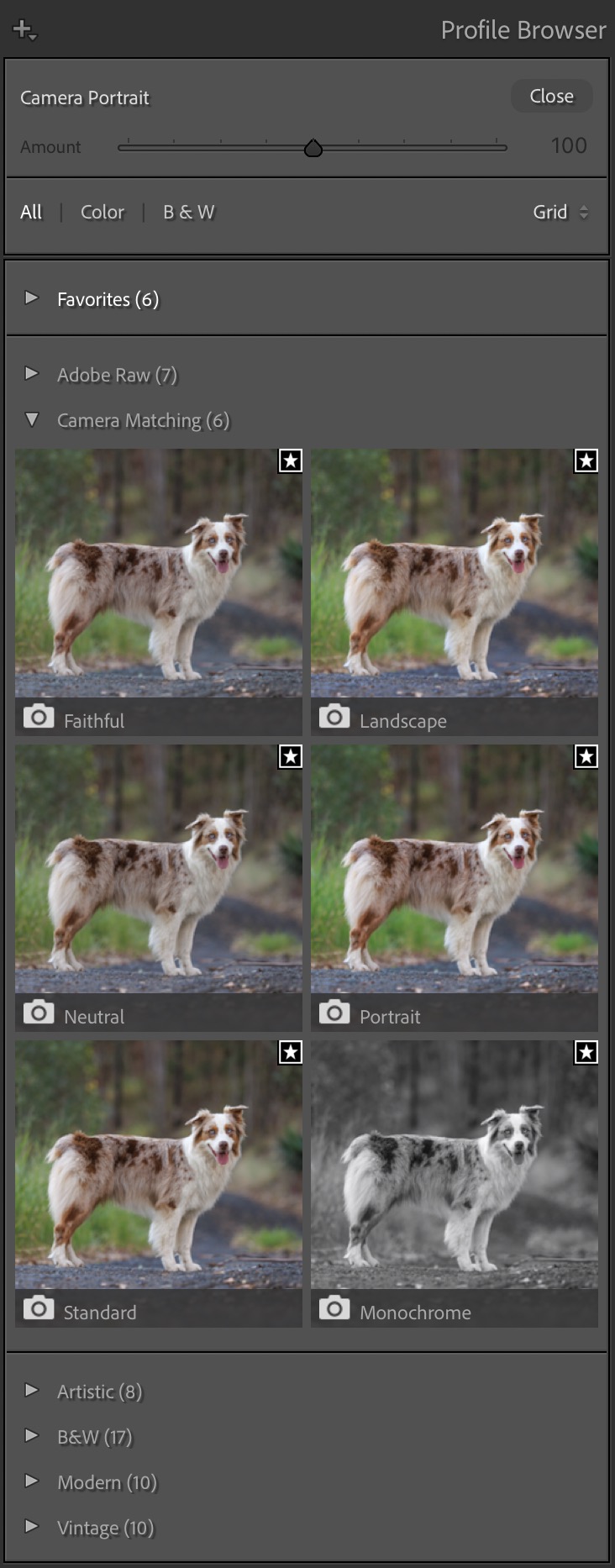

If you’re shooting RAW, it doesn’t matter! You can choose the profile that you like the look of best on the back of your camera. When you import your photo into Lightroom you can have it automatically apply your favourite profile (find out how to do this here). If you want to change this while you’re editing, you can flick through all the available profiles on your computer to see how your image renders for each one, and with no penalty. You get to choose the recipe and tweak it to your particular taste.

You can preview how your photo will look with any of the profiles in Lightroom’s Profile Browser. Note that these aren’t presets, although can be easily confused with them. These are simply “recipes” on how to present the RAW data from your image before you start editing.

If you’re shooting in JPG, however, it’s more of a concern, because you’re baking in that recipe at the point you take the photograph. And this means that if you have a landscape-specific profile chosen and then you photograph a person, they may look a bit orange, and there’s not much you can do to correct it after the event, because that cake has already been baked, even though you might have actually wanted a muffin.

Of course, you could change your profile every time you photograph something different, but you still won’t have the control to fine-tune the results to your taste. And don’t we have enough to think about anyway?

This was shot in JPG with the Camera Portrait camera profile selected. The greens are rather hideous and the warm tones are lemon-y, wouldn’t you agree? And very difficult to fix when editing the JPG.

The same image shot in RAW, with the Camera Standard profile applied in Lightroom. Much more true-to-life greens and the yellows/oranges are warmer and more accurate. Note also all the extra detail available in the bokeh highlights. This is due to increased dynamic range in the RAW file.

And what white balance should I set the camera to?

Again, if you’re shooting RAW, the white balance you choose is not set in stone in the RAW file. The raw data that is captured includes every possible white balance “ingredient” so you can change it to your heart’s content when you are editing. Whatever white balance you set, it will look super accurate and have no loss of quality and usually no weird colour casts. We mostly just leave it on Auto (AWB).

If you’re shooting in JPG though, beware! The white balance you set is baked into the image and trying to adjust it in the editing stage will not give good results.

This image of Fletcher was shot in RAW on Auto white balance. It’s quite blue (cold) but since it’s a RAW file, it’s possible to quickly and easily correct the white balance in Lightroom.

Here’s the corrected version. The only thing that is different is the white balance. And how much more true-to-life does the image look now?

Here’s the exact same image, but this one was shot in JPG. The white balance has been adjusted, however, it’s just not possible to get the same “correctness” in the colour without introducing colour casts. The Tint balance between magenta and green is especially tricky. Also, notice how much less detail there is in the highlights (the bright areas of bokeh) and see the blockiness of the blacks in Fletcher’s face? This is due to the reduced dynamic range of the JPG file straight from the camera.

But what if I don’t know how to edit?

If you don’t know how to use Lightroom or another RAW file editor (and, let’s face it, no-one is born knowing), then it may be a good option to stay shooting in JPG for now. This will allow you to instantly have images that you can share. Go through your camera’s profiles and choose the one you like the best (we would recommend the standard one, but your tastes may vary), and every photo you take will be baked to that recipe. Just make sure you have the white balance set as close to correct as you can.

If you think that you might be interested in experimenting with RAW files, but still want the convenience of instant JPGs, then set your camera up to have the best of both worlds by choosing the “JPG + RAW” option in your settings. With this selected, every time you take a photo, it will create both the RAW file and the JPG image. If you start to dabble in Lightroom, you can experiment by seeing what changes it’s possible to make with the sliders on the RAW file compared to the JPG.

If you do want to learn how to edit your pet photos, here at Unleashed Education, we can help with that! We have a tonne of resources, both free and paid, that show you step-by-step how to use Lightroom and Photoshop to edit your RAW files and get amazing results.

And what if I don’t WANT to edit?

We hear this quite regularly, that people don’t want to create over-processed fantasies. We should all get it right on camera, right? Right. We’re not about to disagree with learning the skills to make a properly exposed, focussed, and composed image in camera: that’s our jam! Beyond that, some people choose to use more artistic licence in enhancing their images than other people do. If you’re someone who strives for the “natural” image, then this idea of not wanting to edit may resonate.

However, I’m going to burst your bubble just a little bit: by shooting in JPG only, you are letting your camera decide what that “reality” looks like. Revisit your profiles. You choose a landscape profile and the greens are suddenly more vibrant. You choose a monochrome one and everything is displayed in tones of grey. You choose a portrait one and the skin tones suddenly come to life. Which of these is “reality”? You have to choose because your camera can’t. It can’t bake a JPG file without a recipe to follow.

Someone far brighter than me once told me, “You are smarter than your camera”. I’m still not entirely sure if that’s true, especially considering how quickly camera technology is progressing, but one thing that is certain is that our cameras don’t know how we feel about any scene that we’re shooting. They don’t see the same way we do - with all our senses, experience, and emotions. A sensor is not built the same way as our eyes and brain, and they can’t make the interpretations that we do when we’re immersed in a scene. The camera doesn’t know if we want to emphasise contrast, saturation, or whether we feel it as a more muted scene. Our cameras can only read the light hitting the sensor, they simply don’t experience the moment as we do.

By shooting in RAW, we get to make the image look exactly how it looked to our eyes in the moment.

When I shot this image of Enzo, the late afternoon light was streaming into the garden and his puppy floof was warmly backlit. The RAW file doesn’t show that, however since all the data is available in the image, it was possible to edit and “bring out” the warm, bright qualities lurking within. The image was deliberately underexposed to preserve the detail in the very bright highlights.

In the edited version, Enzo is beautifully backlit, with the rimlight around him not blown out and his fur perfectly white. There’s plenty of colour in the purple blossoms and the image looks warm and beautiful, but still true-to-life. Shooting this image in JPG would not have preserved the full ranges of tones present in the scene, making an edit like this impossible. You can watch part of this edit here.

Need more convincing that shooting RAW is the better option if you plan on editing your images?

Let’s get our geek on and talk about bit depth.

While this at first seems more related to mathematics than art, it is definitely something that’s worth knowing a little bit about as it directly affects the look and quality of your images.

Bit depth, essentially, relates to the number of colours that an image can store. One bit equals two colours (black and white). Without getting bogged down in the details, a JPG image is 8 bits and can store 256 tones on each of three “channels” (red, green, and blue), for a total of around 16 million different colours.

That may sound like a lot, and it is! It’s enough that JPG files generally look great, with smooth transitions in gradients of colours.

A RAW file, however, usually has either 12 or 14 bits, which equates to over 68 BILLION or 4 TRILLION colours!! Now that is a lot of colours!

This difference shows up markedly when you try to adjust contrast or colours (white balance especially) when you are editing the image. With JPGs, you’ll often end up with ugly colours or banding and posterisation effects, especially in areas of gradually changing tone, such as the sky.

So even the process of your camera saving the image data to a JPG file immediately throws away billions of colours - colours that you could manipulate to create your beautifully edited masterpiece!

Banding is present in the sky of this image, which means there’s just not enough colours available in the JPG to give a smooth transition of tones when the tones are edited. You can avoid this by shooting in RAW and doing all your edits to the RAW file!

What is “lossy” and how is it bad?

Finally - wowzers, this has been a long one! - comes the issue of file degradation. JPG files are what’s called a “lossy” file type. Every time you open, edit, and save a JPG image, it will be compressed a little bit more, meaning you’ll “lose” some data. So if you shoot in JPG, and then continually close and open your JPG in destructive editing programs like Photoshop, you are killing the quality each and every time you re-save it. Over time, you’ll notice it becoming fuzzy or weird artefacts appearing.

The same is not the case with a RAW file. In fact, when you manipulate a RAW file, you don’t actually change the file itself at all, but rather another file is created which holds all the instructions of the manipulations you’ve made to it - the recipe file. Only when your recipe is applied and it’s exported to an actual image file for sharing that your edits are baked into the resultant JPG.

Your RAW file will remain in the exact same pristine state as the day it was captured by your camera’s sensor. Now THAT is smart!

To summarise, I think it’s clear that we are very much in favour of capturing our photographs in RAW format rather than JPG, because doing so gives us so much more control of how the scene is interpreted by us, without leaving that decision up to our camera. It gives us the ability to tell the story of our images more precisely, and to evoke the same feelings in those people viewing our photographs as we experienced at the time we captured them.

We really hope that you enjoyed this discussion on the pros and cons of RAW and JPG capture. Have we convinced you to give RAW a try?

Any questions? Drop them in our Facebook group!

Ready to test your knowledge? Complete the quiz!

Join our mailing list!

Want to improve your pet photography with free tips and expert advice?

Join our mailing list and get a guided tour of what we have to offer, along with our weekly newsletter packed with practical pet photography insights.

📩 Sign up now and start learning with us!

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.